“Nobody with hope joins a gang,” says Brian Zater, the Lebanese Jewish Zen Monk of Glass House. He’s telling me about his first encounter with a White Nationalist, “He was covered from the neck down in tattoos, with plenty of swastikas.”

Brian Jones approached Zater, the new guy in the Pen, in a TV room known to be a blind spot from the cameras, where Zater was doing some paperwork on a table.

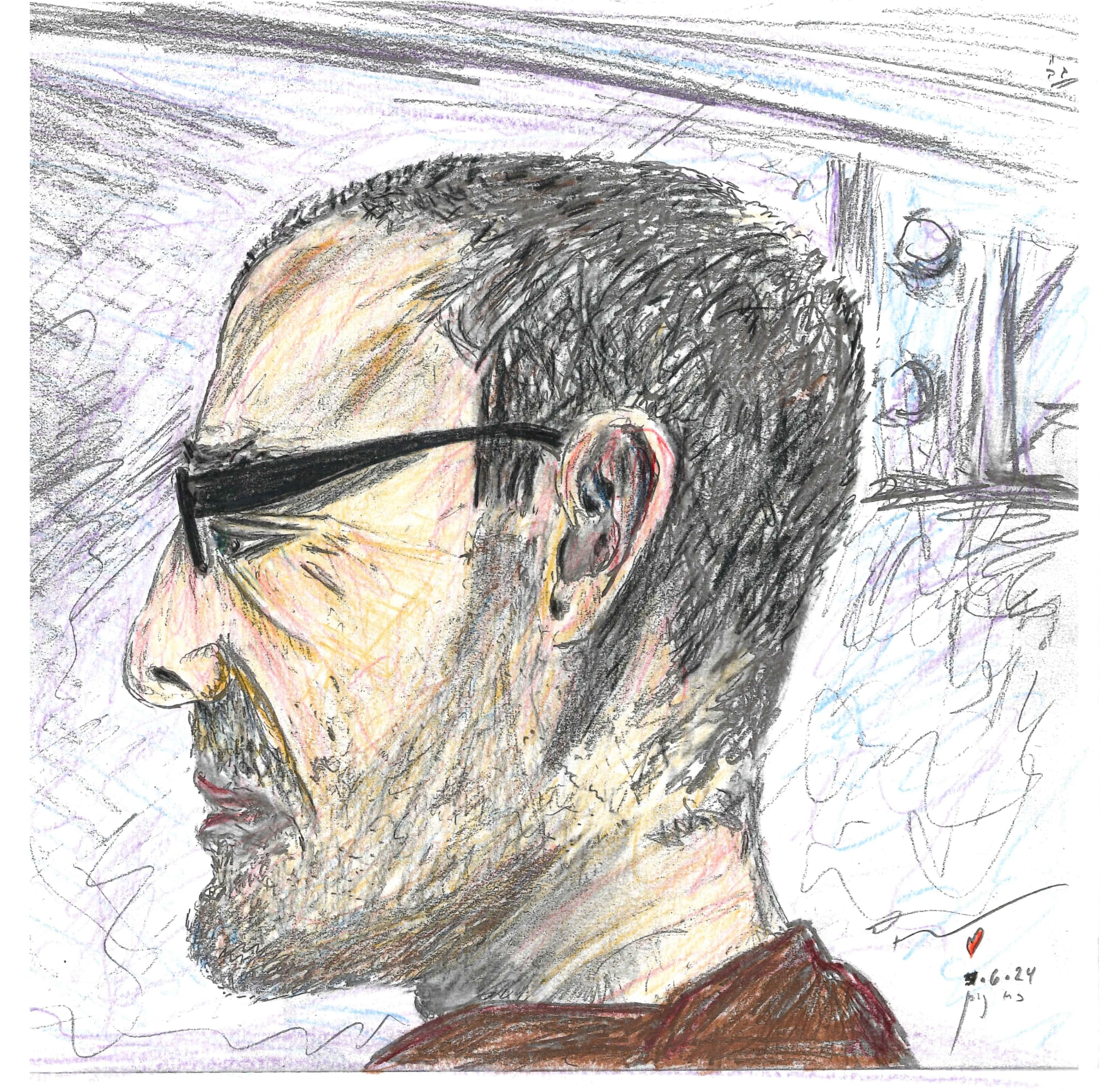

“I’m here to do a heart check,” Jones said to the stocky Zater, 5’6″, head buzzed to a #2, and his Unicor t-shirt packed with solid muscle.

A heart check is a fight—to see if you’ve got the heart in you to fight back.

“I had two things going for me. I was Lebanese, and the white guys didn’t know what to do with that, and my paper checked out. I wasn’t a rat or a ChoMo (child molester),” Zater explained, “So they do a heart check.”

“It’s not a surprise. He’ll announce it. They assign someone from each group to come fight you, to see if you have the willpower, if you have your heart in it.”

Zater, who spent the first months of his incarceration for multiple armed bank robberies in solitary because he was “red dotted,” signifying his martial arts and combat training made him a higher threat than the general population of murders and gang members, pinned Jones easily.

A few days later, Jones approached him. “You want to go again?” Zater asked.

“No, I’ve never had anyone handle me like that. Can you teach me?”

“I figured it would be a way to get into his mind and help wake him up,” Zater explained. “And I had to prepare myself because I’d never taught formally. I’d only learned and trained for myself. I was interested in the combat, not the teaching, when I was younger.”

Zater had reason to learn to fight. His father, an Army Ranger, beat him and his younger brother brutally on the regular. Dad was 16 when he lied his way into the military, and not much older when he returned from Korea with a clear case of PTSD.

“I think being beaten regularly as a child makes you develop the ability to dissociate,” Zater says. “You learn to not go with the flow, to not trust everything you’re taught. I’m deeply wary of groupthink. I’ve never been a joiner. I’ll participate, but I don’t just follow.”

Zater is a leader. This invitation to teach, a Jew teaching a Neo-Nazi to fight, led to Zater being the “Tony Robbins” of the Federal Penitentiary.

In fact, Zater, a prolific writer, wrote to “Anthony Robbins,” as he calls him in the respectful tone of a man raised by a military dad and decades of the BOP system. Robbins loved his letter and sent him every book and program he could. Zater vacuumed the information and internalized it. Then, he taught.

His classes, to men covered head to toe in tattoos espousing all sorts of hateful and violent ideologies and groups, were “sold out.” Hundreds of men took the courses. Many regained hope despite long and even life sentences. Those fortunate to get out, back “on the streets,” never returned to prison. All but one became successful entrepreneurs and the one who didn’t has a secure job. They are family men and community leaders who help others stay out of prison, too.

One young man, a neo-Nazi named Jason Burk, became Zater’s student and now serves as his research assistant on the outside. Zater, who is now my neighbor at the Glass House in FCI Miami, helps many men file for compassionate release and do other legal work inside. Burk, a tech whiz, helps him find the information.

Oh, and Jason isn’t a Nazi anymore, he’s a Jew. And he always was.

“I don’t believe in coincidences,” Zater says. “Jason did the work, elevated his state, and manifested his birth family looking him up and finding him in prison.”

His mother, who had to put him up for adoption, was Jewish. Burk, covered in swastikas, discovered that not only was his prison mentor and savior Jewish, he was too.

Burk was an orphan, as was Jones. Without stable parents, they found “parents” in these hateful gangs. It’s a common theme you see in prison. A divorce, a death, a foster parent that’s abusive—Burk’s mom was a literal crack whore—and boom, a kid takes a dark turn. Prison reminds you daily that, “but for the grace of God…”

Jones took Ohio State correspondence courses, together with Zater, who has an insatiable appetite for learning.

“The professors were like, ‘Who is this guy?’,” Zater says of Jones, “He wasn’t just good at math, he was off the charts. He took math and physics and got a degree. I got a company to pay for the degree. I wrote to a hundred companies and one agreed to sponsor it.”

You’ll hear some soul-crushing, mind-numbing repetitive task mentioned in almost every conversation with Zater.

You cannot just mail merge 100 letters in prison. There’s no Microsoft Word, no Google Docs. He had to type a letter on an electric typewriter, let the machine type it out, save the text electronically, go back and edit the names on a tiny monochrome screen that displays only a few lines at a time… and do this over and over, perfectly, 100 times. Electric typewriters type slow—for those of us used to laser and inkjet printers this would be torture.

Zater did something similar for Ollie, the older man who makes realistic boats out of Styrofoam food trays, popsicle sticks, and thin strips of wood. Zater was in facilities and stood at the table saw cutting thousands of thin strips of wood for Ollie. In exchange Ollie made a boat for Zater’s dad—Zater and his father healed their relationship and are close now.

I ask Zater, “What does it feel like when you’re at wood strip one thousand and twenty and your mind is just numb from the repetition?”

“I like doing tasks where I get to the point that there’s nothing I hate and want to get away from more—and that zones me in,” Zater says with conviction and force. “I explore the feeling and use it as a fuel source.”

“That feeling is a Comfort Zone Wall,” he continues.

“Take your hands and cross your fingers like this,” Zater says, showing his fingers interlaced, one thumb atop another, palms together. I put my pen down and do it.

“Notice your left thumb is over your right. Now try it the other way. Notice how awkward that feels? That’s the feeling of being outside a Comfort Zone Wall, and it’s the inability to have or sustain that feeling that keeps guys in prison.”

Zater draws a square about 2 inches wide on a yellow legal pad. The table in his Glass House cubicle is full of pads and papers, mounds of handwritten legal briefs and research to be typed later. It’s a sea of yellow and white.

“These are the walls of your comfort zone,” he points to the square. “Most people never leave this. They’ve done studies. People have 47,000 or so thoughts a day, and they’re the same every day. Most people are zombies. Walking dead. But once you confront the Comfort Wall Zone, once you push past it, your walls expand.”

Zater draws a square an inch around the smaller square. He points to the small square. “This is scarcity. This is where most people stay locked in, imprisoned.”

“Every guy who comes back to prison, it’s because they couldn’t get out of this box, they couldn’t expand the box.”

“That’s transcendence, that’s the point of Judaism,” I offer.

“King David talks about this all the time,” Zater says without missing a beat, “I wrote down a list. He mentions so many times in Psalms how he was facing discomfort, distress, anxiety, and he turns to God and God expands his space, brings him into an expansive state. It’s all over his writing.”

Zater is the Lebanese Jewish Zen Monk Rabbi of the Glass House, it turns out. And, of course, he’s compiled a list.

“You realize the beauty of this metaphor?” I ask, smiling. “We’re literally in a prison, the definition of being boxed into a small space. You’re here, but the walls don’t contain you.”

“You cannot maintain freedom on the outside if you cannot maintain it within.”

“The guys who come back,” Zater gets adamant, his tone filled with a hint of pain, “They stay in the scarcity box. ‘I’m too old’…’I’m black’… ‘I’m a victim’… ‘I was abused’… ‘I’m a convict…’ Most men are in prison before they get here, and they stay there when they get out.”

In the flow of our conversation, he mentions a man who did get out.

One feature of Zater’s stories is he’ll toss out some incredible fact or tidbit without realizing how exceptional or interesting it might be to the outside. That’s fair—he’s not been able to get rapid, direct feedback for 20-plus years. Only a few high profile white collar guys are put into the Pen and only due to long sentences of hundreds of years, but in our conversation Zater mentions one, “Shlomo.”

Shlomo was Zater’s neighbor at the Pen, and Zater was one of his “Commissary Guys.”

Guys without funds often have their commissary sponsored, via the outside, by those with means. In this way, you can order more food and supplies than allowed by your monthly max ($360). For those who keep kosher, being able to buy more tuna, rice, and other kosher items helps supplement a more-limited diet. Guys will often “trade” weeks, so that someone who’s hit their max can still get food a week earlier, and they’ll return the favor or repay it another way.

“Shlomo was incredibly family oriented. He had this calendar he made, with photos of his family, and he was very careful to maintain it, to follow up on the dates, the birthdays, anniversaries. I don’t know what he was like on the outside before his sentence, but on the inside he was all about family.”

Zater talks about the dangers of a “Pen” or high prison, especially one with “DC Guys” (DC is not a state, so a wider, more-violent array of men who commit crimes there end up in the Federal system) and how Shlomo befriended those who could protect him.

When there wasn’t a lockdown. Lockdowns were frequent. Zater describes the pen as, “the Thunderdome in Mad Max.” Yet, when there was a peaceful Friday night, the Zen Monk of Glass House and Shlomo would join their brothers and welcome Shabbat.

Zater, too, has found his way out, getting his 50-year sentence reduced by 15 years, and now hopefully another 5. He’s working to reduce the related state sentence, so he’s clear and free across the board (State prisons, he says, are much worse than the Feds). They are hoping he’s out by this time next year.

I am sure in a few years you’ll see Brian Zater on stage, right there next to Mr. Anthony Robbins, showing thousands of people, and then millions, that there is no confinement if you free yourself from within.

With love,

Ari

###

Draft 1.2. Some numbers, quotes, and spelling may contain errors.

edited to correct (Shlomo was not Sholom Rubashkin).

You may share this group email.

Leave a Reply