Joey (name changed) twitches like a lovable toy robot dropped down the stairs a few too many times. The batteries are fully charged, but jerky movements let you know something’s loose inside. Still, his smile radiates with a shy glee and his eyes [reveal] a brain working overtime. It doesn’t tell him nice things.

“I was on meth, and doing a lot of bad shit,” he says, a twinge of local Florida accent coming through. “It was not good.”

He’s in on an “S.O. Charge”, a sex offender, known inside as a “ChoMo” case.

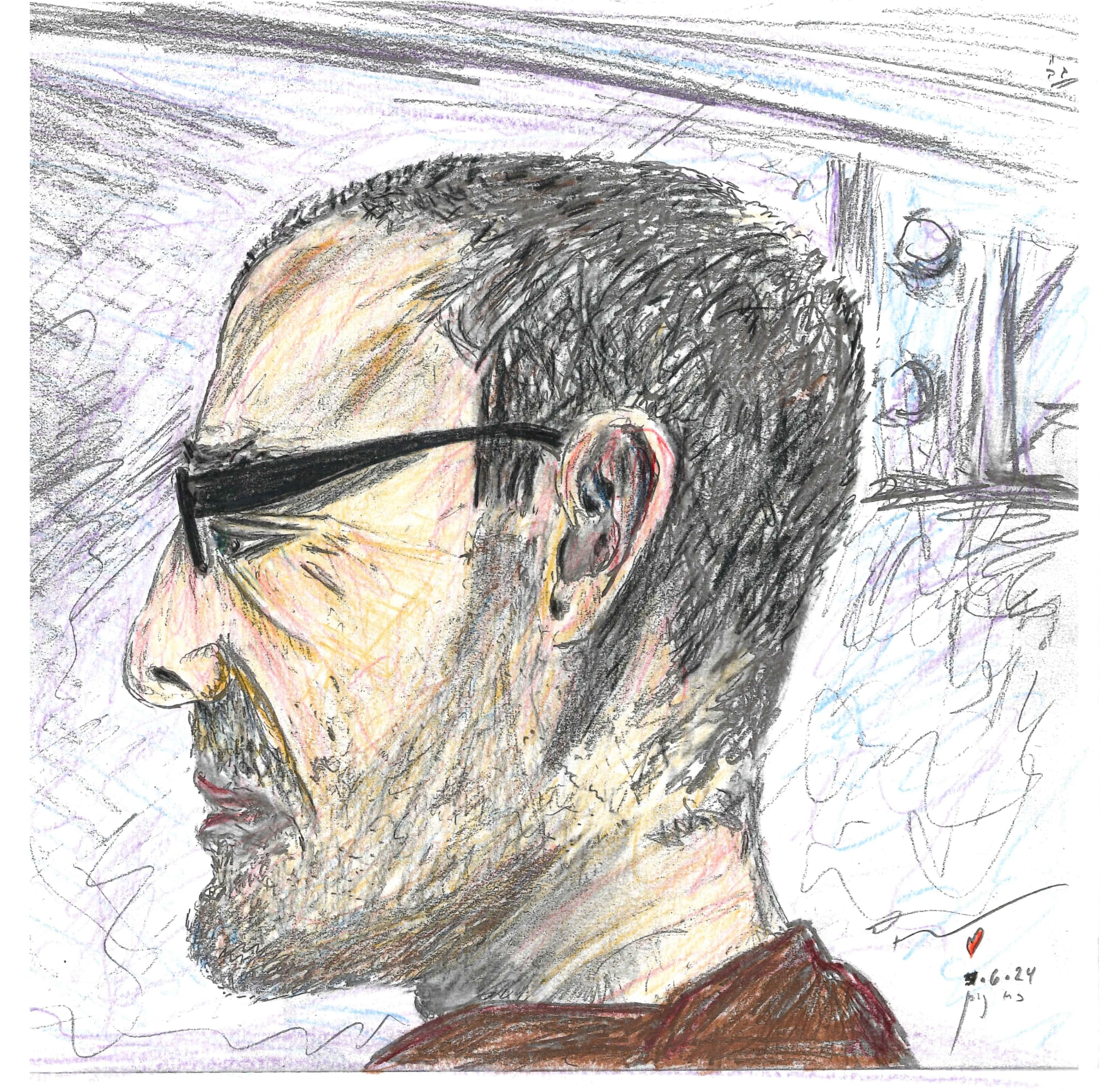

At 26, Joey is one of the younger men at FCI Miami, where it’s not unusual to see gray haired men hunched and hobbling down the path with walkers and canes, and where most men seem to fall in their 30s to 50s. His colorful glasses and gaping earing holes testify to his life of music… and his path to addiction, a battle he has been winning lately.

But addiction makes the other men here wary. Young junkies and ChoMos inspire an ambivalent mix of hope and despair. The men inside want these guys to win, to heal, to prevail, but are often repulsed by their past actions, afraid to be associated in many cases, and have been burned from many relapses, not only theirs, but those who came before him. Failure is a powerful reinforcement, and drug relapse rates are high. (Editor’s note: Men in for sex offenses actually have one of the lowest recidivism rates.)

But faith doesn’t care about odds, each person is unique, and our job isn’t to judge, so I take this opportunity of being at a Low (there are no SO’s in a Camp) to get to know the ChoMos, something that might get you beaten or killed in a Medium or Pen.

A man down 20+ years explained that at a Pen, gangs are handed paperwork by the guards and assign a man to beat the sex offender upon arrival, whereupon the gang (or gangs) join in and stomp the offender until they die or the guards, waiting in the wings with riot gear and bear spray to break it up and medivac the alleged offender off the compound, a message to Grand Prairie, BOP Central, “Do not send these cases here.” You cannot turn down the gang’s assignment. Beat or be beaten. This applies to the guards, too.

The hatred is understandable. It is easy to cheer for the bank robber who redeems himself, the drug dealer who gets clean for his child, and far more difficult, viscerally and intellectually, to root for a man who preyed on children or watched the product of others who did.

And yet, if we are to cure this disease, we must speak with these men and understand them. Unless we are going to lock them up for life, or send them to their deaths, it is in our interest to help them heal the pain and overcome the urges that landed them here.

Religiously, we are all pure souls in bodies, and that applies to these men, too. Killing them or torturing them, while understandable, not only fails to move us closer to an effective treatment and prevention of further cases, but deters communities and families from reporting abusers. It is far more difficult to send a family member or friend to be tortured and killed than to send him to a safe campus away from children. It is even more inhumane once you get to understand the root of the abuse.

There are three categories of “ChoMo” cases, by my observation: The first, are guys who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. They got duped into exchanging photos with a minor who lied about being 18+, or forwarded a link, or downloaded a folder without knowing what was in it.

There are the cases of a 19 year old arrested with a 17-year old in a state with no exceptions and a prosecutor who arguably abused their disgression. Some guys claim someone else used their computer or network at home or work. Many guys use these excuses, and most are lying, but in a few cases it must be true. There are two guys here we all believe, and a few others who might be truthful.

The second, most common at FCI, are guys who give off an energy you can sense — an “arrogant insecurity”

masking buried rage. They are, by-in-large, overtly friendly, but turn quickly. If you think about that principal, counselor, coach, priest, rabbi, or other person in position of power who was revealed to be abusive towards children and teens, you know the energy. It is shockingly common.

The third, far more rare but impossible to miss, are the guys you can see from a mile away whose physical appearance, gait, and behavior tell you something is wired terribly wrong. Often, within seconds of hearing them, you detect a low-IQ and deep disconnect from reality. These men are unwell, physically and mentally. You wouldn’t leave your kids with them out of instinct. They can barely care for themselves, and many are in wheelchairs — sometimes from being beaten into them at harsher prisons, but often because their systems are falling apart.

What is reassuring about “Category Two”, the most common by far, is it appears fixable, and they all seem to share the same pattern.

Most of these men, like Joey, have parts of themselves which say loudly, internally and externally, that they’re not good enough, not wanted, not capable, that their feelings and needs aren’t valid. Their discussions of the future are colored mostly by their past, by why they’re unable to do something, or by a thing or things which went wrong.

They are grown men, but very childlike in many ways.

“I hate exercising. My feet hurt. I have bad feet,” Joey says when I encourage him to start going to the rec yard regularly.

“So do pull ups.” “I don’t like it.” “Have you tried?” “No.”

“The strings on the guitars are all bad, each one is missing a string,” when he tells me he loves to play guitar but isn’t practicing.

“So swap a string from one to another.”

“I don’t know how.”

“There’s a lot of time here to figure it out, and they’re not being used anyway.”

“But people bother me, I want to just play alone.”

“So practice assertiveness and tell them you’d just like to practice alone.”

“Ok.”

These excuses have stopped him from working out and practicing for months, but they aren’t insurmountable. A day later, Joey comes in beaming. “I made it to rec. I hated it, but I walked the track and did some weights, and then played guitar. The strings suck.”

His face has the smile of a child looking for praise. At 41, I’m the big brother.

“Great job. What time are you going tomorrow?”

“I’m not. I hated it.”

“So find something you like. Break the resistance. Break the excuse.”

A week later, Joey is beaming, and a regular at rec. His energy and mood are up. The voice that told him he couldn’t, silenced. He may relapse, but he’ll know it’s doable.

More importantly, he has an activity to pursue that isn’t drugs, an escape in the form of a guitar instead of K2.

Making excuses to avoid exercise or practicing an instrument may feel unrelated to sexual offenses or drug addiction, but I suspect it’s not.

Every addiction is an escape, an avoidance.

“My therapist told me, ‘You gamble to avoid life’,” Norm MacDonald once joked, “I said, ‘Isn’t that why we do everything?’”

Yet there are healthy escapes and ones that land you in debt, the hospital… or prison.

The compulsive gambler, smoker, drug, food, or sex addict is avoiding life, distracting themselves from facing their challenges and demons.

This is weakness, the ingredient all of these behaviors share.

Almost everyone is in prison not because they were strong, but because they were weak.

Jordan Peterson’s lines stand out to me in these moments. “You should be a monster, and then learn to control it,” he explains. “If you’re afraid of what strong men can do, wait till you see what weak men are capable of.”

It is the weak men who abuse the vulnerable. It is in moments of weakness that people take on a scarcity mentality and steal, escape through drugs, or abuse someone else.

Strong people do not hurt others.

“I stuttered a lot,” says Ryan, a newly-arrived Jewish inmate, on his last of nearly 14 years in prison for picking up a 12-year-old who (prosecutors agree) claimed she was 16 in his car after chatting with her online. He was 23.

Ryan has lots of excuses, “It was normalized to me, my girlfriend was in college when I was in high school… my brother dated a girl five-years younger than him… I stuttered a lot and was very shy… my girlfriend was cheating on me…”

All of these may be true, but so is knowing it’s illegal to meet a 16-year-old for sex when you’re 23.

“Was there a voice that told you not to do this? That said it wasn’t right or worth the risk?” I ask.

“Yeah.”

That voice not being strong enough to overpower the others. That’s the weakness I’m talking about.

The inability to simply say, “I fucked up. I made a huge mistake. I needed help and I’m getting it,” that’s the weakness I’m talking about.

And we all have it. We may not manifest our weakness in the same way, and thank G-d we don’t, but all of us have hurt someone, made an excuse, shirked responsibility, told a lie, rather than face our mistakes and battle our demons.

I wrote about this with Reuven’s voice and my failure to stop my girlfriend from pursuing an abortion, an eternal failure on my part with traumatic consequences. My weakness wasn’t illegal, but it ended the life that would be a beautiful and wonderful child and caused tremendous trauma when all I needed was a little more strength, a lot more faith.

Weakness of this kind is toxic, and takes us to bad places, but it is curable. We can find our voice. By facing our traumas and pains, by wrestling ourselves to face our pained parts, and coming to peace with them, we can regain it. We can find our true Self, the part of G-d inside us that always knows what is right, the voice we follow when we are at our best.

This, I believe, is the “cure” that can prevent generations of victims, or folks who are stuck seeing themselves as victims, from victimizing others.

And this, too, is why these men should be treated with love and compassion, not more pain. Killing someone who abused children or locking them in a cage for life is understable, and it might be our only option now (never killing — the temptation to an aggrieved ex to falsely accuse someone is too high, and America’s death penalty conviction error rate is already well over 10%!), but it is a weak one. We must become stronger so we can help these men find their strength.

A cage is admitting we are not strong or skilled enough to heal someone. It is quitting — and that’s the easy way The American prison system has a high recidivism rate because it misses the core message of G-d about Tzedakah, which is often translated as “charity” but comes from the word “Tzedek” or righteous. Tzedaka is about making things right.

The two highest forms of Tzedaka in Judaism, according to the Rambam, are, #1, Pidyon Shvuyim, redeeming a captive, and #2 investing in someone or giving them a loan or job *so they can become self-sufficient*. The highest act one can do according to the Torah is lift someone up so they can lift themselves — and these laws, between humans, outweigh and precede any gift or act we can do “for” G-d. In fact, one is required to use funds meant for building a synagogue to free a captive, and to put freeing a captive above even feeding the poor.

Freeing a man from captivity is #1.

And this must, in our modern era, include the prison of the mind, the prison that is trauma, abuse, and the false, negative things men tell themselves that keep them in a state of weakness.

We must fight the “weak”, in ourselves, in our systems, and in our brothers.

Rabbi Sacks asks, about the Torah portions detailing the construction of the Tabernacle (“Mishkan”) and holy vessels, why so much attention is paid to them, why so much of the building material must be given voluntarily, and, ultimately, how can we even build a “home” for an infinite and eternal G-d who exists outside of the bounds of time and space? The answer is that it is not in the physical building, but in the act of building that we create a space for G-d. Not in the building, but in our minds and souls.

It is difficult and daunting to imagine a project to treat and heal these men with compassion and love, but that is our Tabernacle, that is our making space for G-d.

Dr. Richard Schwartz, founder of IFS, writes in No Bad Parts that when he worked with abusers he found a pattern. Many of the men were victims of abuse and, as small children, had internalized the rage of their abusers, forming a part that projected that rage outward. This is the rage you see under the joyful demeanor of the Category Two folks, and it exists in the Category Three as well.

So, ultimately, when we seek to punish a man for abusing a child, we are also punishing the abused child in that man.

Martin Luther King Jr said, hate cannot cure hate, pain cannot cure pain.

Continued…

(Continued from Part 1)

To end the cycles of abuse we cannot heap pain on top of pain. Only love can solve this. People in pain must see a path out *other* than their “escape”, be it abuse, drugs, or any compulsion that hurts others and lands them in prison.

The statistics speak for themselves. Harsh punishment does not cure or deter negative behaviors. In fact, it often multiplies them.

These men have parts which tell them many times a day that they are unlovable, unwanted, and not OK. These parts project the hurt and rage they experienced as vulnerable children onto the next generation of vulnerable children.

To respond to them with our own rage doesn’t fix anything, reinforces their negative beliefs about the world being a painful place, and keeps us stuck in this lower energy.

Prison should not be a place of pain and suffering, but of love. It should greet you with compassion, saying, “You have a soul inside, a part of G-d, which is pure and well-meaning, and we are here to help you find it, find comfort in it, and use it to comfort and coach those parts which are hurting and acting out of control. We are here to give you strength to control and guide yourself to better choices and better days.”

Instead, we lock them in a cold, dirty, painful cage, rip them from their families, and destroy any good they have in their lives. Then we wonder why they relapse.

Inside every man in FCI is a kind heart who helps his brother, and looks out for a stranger, who seeks to improve.

They offer advice, friendship, and help you with nearly anything you need — whether you are a stranger or friend, new or old timer, no matter your race or religion.

They are not saints, they are not always kind, but they are kind more often than they are not.

There is far more strength in each man here than weakness, strength to overcome prejudice, fear, trauma, addiction.

They just don’t realize it… yet.

This will not be easy. Facing your demons rarely is.

Many of these men have extreme patterns of lack of control, and it extends beyond their charges. Facing imminent health issues, many cannot control their eating, or limit it to a clean diet. Facing the SHU and years more in prison, they cannot stay away from drugs. Most do not exercise regularly, despite being physically able.

Their testotestrone levels seem low (a common observation, at least) but just low enough that they could be boosted by lifting weights, eating healthier foods, and getting into better shape. This, in turn, will help them control their moods and behaviours.

Verbally, too, patterns of negative self-talk can take months or years to change. The idea is easy, the execution and development of habit takes time and effort. Persistence more than inspiration.

Self-control is the first battlefront.

It is not an easy task, surely, but as as Rabbi Tarfon teaches us in Pirke Avot, “You are not expected to complete the task, nor are you free to desist from it.”

This work, the difficult work of uplifting ourselves and others, is our Mishkan, our making space for G-d.

By now it should be obvious to you that these patterns are not limited to men arrested for abuse, or any other offense.

Weakness is found not just in the men “inside” but throughout society. Time and again you meet an officer who is “just following orders” despite ackowledging injustice. They could speak up and end the injustice, free the victim of abuse, but they fear the loss of a job or promotion or pension more than they fear doing the wrong thing, more than they fear perpetuating evil.

Our society must work to give these men and women strength to speak up, to encourage them to find their souls’ voice and end injustice. Injustice feeds on weakness, not only of the victims but the perpetrators. Men need the confidence to feel they will be OK if they do what is right. This is faith, the only true strength.

What about the urge to punish? To hurt those who hurt us? A strong society has faith that G-d will balance out injustice, and that He wants us to err on the side of compassion and dignity. Prison will never be heaven, but it doesn’t need to be hell.

This works well in Norway, where recidivism is far lower than in the USA despite more humane prisons, much shorter sentences, and no lifetime sentences or death penalties. The staff there is trained to help men heal and become self-sustaining, to treat them as humans capable of redemption and growth, and the system therefore attracts staff who want to fulfill this mission rather than to cause pain to folks who’ve made mistakes. It recruits strong men and women who want to lift those who cannot yet lift themselves.

There is another reason to make prison pleasant: It will lower the hesitancy to report someone who may be abusing children.

Right now, it’s a heavy lift to report a coworker or friend or family member who might be abusive, because there’s a non-zero chance they will be beaten, tortured, and even killed in prison. They will 100% suffer. I am fighting to breathe every night as I write this, and am only able to write thanks to heavy doses of pain medicine, while my requests for help go unheeded or worse. Men die in prison waiting for medical care they would get in days on the outside. Prison is hell on earth, filthy, full of diseases, mold, violence, and hurt staff (many have PTSD from military service and elsewhere) and incarcerated individuals pouring out more hurt. So it is understandable that friends and neighbors might hesitate to report abusers.

This is bad.

Even if you can’t wrap your mind around being kind to alleged abusers yet, even if you struggle to see their humanity (which I did, too, before living with them for months and experiencing their kindness), you can undestand that were prison a safe, comfortable, healing place, more people might report abuse, telling themselves it’s for the *good* of the abuser and will *end* the cycle of abuse.

“You can radicalize an inmate,” an Lieutenant told me he taught fellow officers. “I gave a class and asked them, ‘Who radicalizes an inmate?’ and they immediately go to the imams and terrorists, but I asked, ‘Can you radicalize an inmate?’ Yes, by how you treat them.”

Pain generates more pain. Rage generates rage. Weakness hurts the weak.

We must fight the weak. We must turn prison — and every institution and family — into a place that builds strength from a position of strength. From faith. From love.

With love, Ari

=========================

Group message. Draft 1.0.

You may share this message.

I have been pretty sick the last few days and it’s been difficult to write and edit, but G-d willing the judge will HaLevi, as the past few nights have been hairy (though I’m pretty hairy anyway!).