This week’s Torah Portion, Mishpatim, is perhaps my favorite. Like a great standup bit, it seems to be random observations going nowhere in particular, until the final revelation. Hot off the giving of the Ten Commandments, we have a Parsha that is different from many which came before it. There are no spectacular miracles, no battles, no crying out to G-d, no prophesy. It is deceptively mundane.

It opens, “And these are the laws [Mishpatim] you are to set before them.” (Ex 21:1) Then it gives a seemingly hodgepodge list of civil and criminal laws: First it tells us a thief sold into slavery goes free in the 7th year [“Shmita”] and if he comes in married, he stays with his wife. If he wants to stay a slave, we bring him before the Rabbinic court, which tries to dissuade him, and we nail an awl through his ear into a doorpost and he stays a slave.”

It discusses in pithy, often one-sentence-or-less statements, the laws of damages from fights, thieves, negligence, bystanders, and animals.

It gets extreme about the dignity of a poor borrower: “If you take your neighbor’s cloak as a security deposit, return it to him [each] night, because his cloak is the only covering he has for his body. What else will he sleep in?

When he cries out to Me, I will hear, for I am compassionate. (Ex 22:26-27)

And strangely specific about a tired donkey: “If you see your enemy’s donkey sagging under it’s burden, you must not pass by. You must surely release it with him.” (Ex 23:5)

And it lays out some classics, “Do not accept a false report… Do not be a follower of the majority for evil… Do not glorify a poor person in his grievance [in court]… ” (Ex 23:1-2) “… Do not pervert the judgement of your poor…

distance yourself form a false word… do not execute the innocent… Do not accept a bribe…” (Ex 23:6-9)

More specifics about unreliable donkeys: “If you encounter your enemy’s ox or donkey wandering, you must return it to him repeatedly.” (Ex 23:4)

And again, “Do not oppress a stranger; you yourselves know the soul of a stranger, because you were strangers in Egypt.” (Ex 23:9)

Then, at the end of these seemingly random, mundane laws, it jumps to talk about sacrifices and revelation: “The choices first fruit of your land you shall bring to the House of Hashem, your G-d; You shall not cook a kid in the milk of its mother.” (23:19) (Another classic! Bye bye, cheeseburgers!)

“Moses wrote all the worlds of Hashem. He arose early in the morning and built an altar at the foot of the mountain… they brought up elevation-offerings…peace offerings… feast peace offerings to Hashem…”

The Parsha ends Moses with ascending the mountain to get the Ten Commandments — something he was giving just last week in Parsha Yitro.

WHAT!?

Why does G-d interrupt the story of Revelation, pausing before the giving of the Tablets, to tell us about small claims court, laws of lending, and the rights of accused criminals and owners of errant oxen? Surely once people accept the Top Ten laws of the Torah they can study the minutia?

And why such “random” examples? What do a slave, handmaiden, an enemy with unreliable donkeys, convert, foreigner, pregnant woman, poor person, widow, a tunneling thief, and an orphan have in common?

Nothing. And that’s the point. In Judaism Nothing can be Everything.

In the ancient world, Rabbi Sacks explains throughout his essays on Genesis and Exodus, empathy was limited to your own tribe. We see this when Sodom goes to abuse Lot’s guests. We see it when Abraham and Jacob fear leaders of foreign lands they visit will kidnap their wives! In fact, we saw the 12 brothers, patriarchs of our 12 Tribes of Israel, fight brothers of another mother. We will read about it soon in the Purim Megillah — Haman convinces Achashverosh to destroy us because our laws and customs are different.

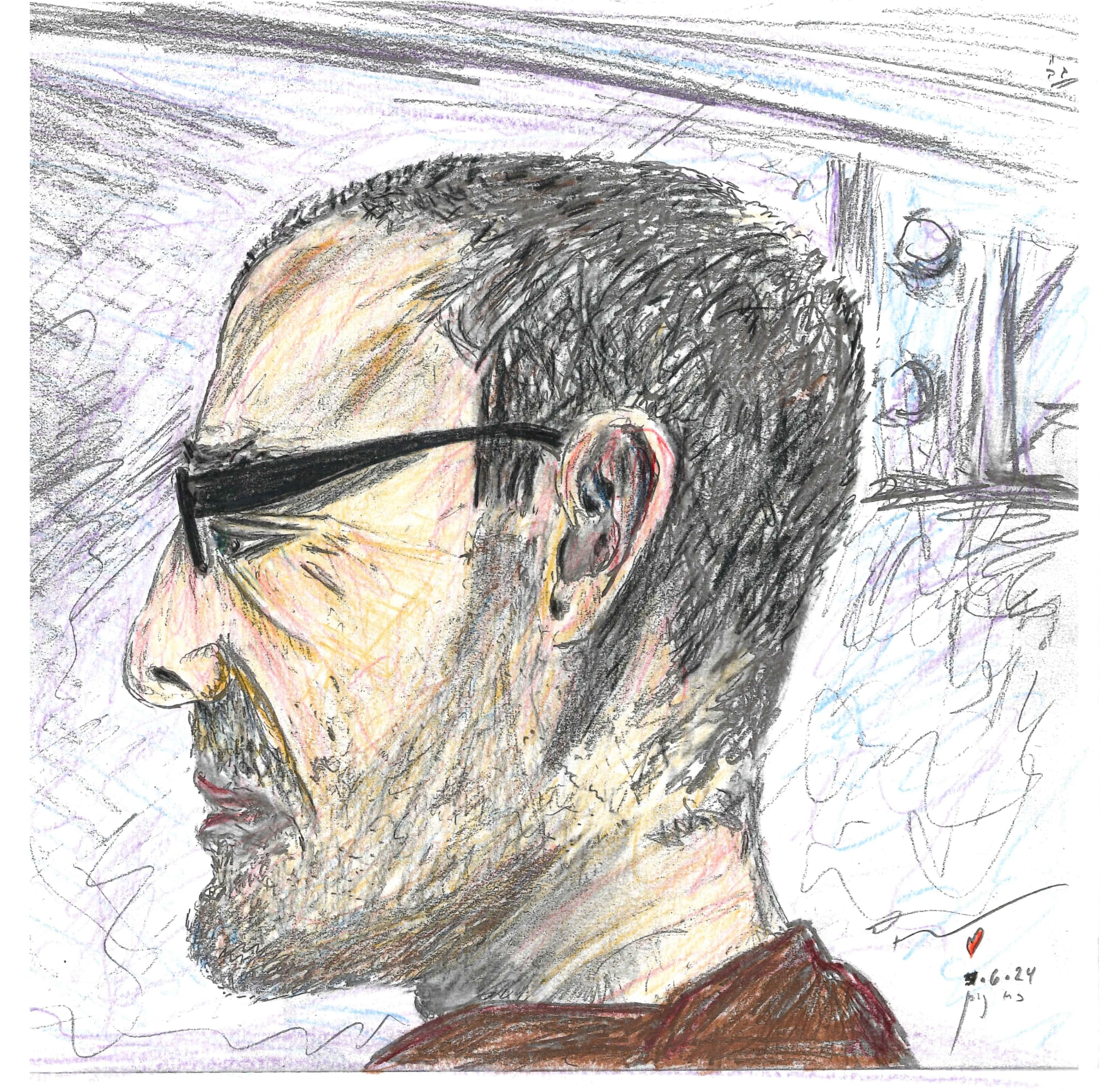

We see this today, too. In prison, a “Cliffs Notes” for humanity in many ways, you quickly see how men in one uniform treat men in another — it’s rarely pretty, we aren’t fully human to the guards. Men “inside” divide by various affiliations, gangs, alleged crimes, geography, and faiths, too (Although I will say emphatically the incarcerated men here see and honor the Humanity in one-another far better than many staff — which will make sense in a minute)…

This isn’t an anomaly — mankind has always jumped to mistreat “others”, and to label and define folks as such.

We have all been guilty of this at one point or another.

But what the Torah tells us is that we must have empathy with folks who have seemingly *nothing* in common with us, strangers, converts, even our *enemies*, because we are all a stranger to someone else. Just as we were strangers in Egypt, we understand what it’s like to feel alone in the world.

We are all going through life alone, each in our own way. We can never truly understand another person’s journey and viewpoint, we cannot feel their pain, we cannot read their mind — not even if they are our parent, child, sibling, spouse, partner, or best friend. No matter how similar we may appear, we are all ultimately strangers to one-another.

In fact, one of the toughest realizations as we age may be that we are strangers to ourselves — there are parts of us we do not recognize or understand, some of which are not ready to be understood.

And *because* of this, we must empathize. With strangers, with neighbors, with loved ones, and with our Self.

BUT! The Torah tells us that logic is insufficient to get to empathy. Empathy does not come from “understanding”.

You cannot think or meditate or pray your way to empathy.

So how do we empathize?

With action.

Rabbi Telushkin asks in Jewish Wisdom: Why does Mishpatim specify “Your enemy’s” donkey? Don’t we have to be kind to any animal crushed under a burden?

He explains that when you come to work with your enemy to lift the donkey, you will see the humanity of him, that you do not have an ‘enemy’, but a fellow man traversing his sliver of eternity alone, with his own set of worries and challenges. You will stop seeing him as a label, “enemy”, and see him as you are: a dynamic, ever-changing human.

The Talmud, Rabbi Sacks explains, takes this further, “If [the animal of] a friend requires unloading, and an enemy’s unloading, you first help your enemy — in order to suppress the evil inclination.” (Bava Metzia 32b)

Judaism does not merely say, “Do not bear a grudge” (though it also does! Lev 19:17-19), but requires us to *practice* peace, to *act* to build relationships and heal division.

It is *logical* to ignore your enemy’s animal or his loss, it is *easy* to rule with the majority, it is *understandable* to say, “I’m not getting involved…” But that is not the empathy G-d demands of us.

Unlike other religions, philosophies, and political schools, Rabbi Sacks emphasizes time and again, Judaism details,” he quotes Danish architect Arne Jacobson, quoting Mies van der Rohe. These small acts of kindness matter, they are not accessories to the Torah, they are the core.

The Sages tell us that intellectual faith without action is futile. Rabbi Chanina Ben Dosa teaches in Pirke Avot (3:12): “Anyone whose good deeds exceed his [Torah] wisdom, his wisdom will endure; but anyone whose wisdom exceeds his good deeds, his wisdom will not endure.”

Whenever there is a tragedy, what brings us together? Not a shared enemy. We had that before they flew into the towers or attacked a concert. What brings us together is when we must work together. There is no Torah without worldly occupation [Derech Eretz], Pirke Avot famously teaches.

Judaism requires acts of kindness, this is the path to empathy…

And where does empathy lead us? Suddenly Mishpatim’s apparent randomness makes sense: Before we can approach G-d with sacrifices (replaced today with prayer), before we can experience Revelation, we must first see the divinity of our fellow man.

Before we meet G-d on the Mountain, we must meet G-d in the strangers who wander into our lives.

How? Acts of kindness.

With love, Ari

======

Group Message. Draft 1.0. You may share this message.