A friend here, Martin, was chatting with me and said his mom was always asking him, “What trouble is you trying to get out of”?

It occurred to me, what if she’d asked him, “What are you trying to get into?”

Are you trying to get into business? A healthy relationship? School? A nicer community? A new skill?

There are really two directions we can be going at any time: Towards or Away.

His community, we continued chatting, has a focus on getting “away”, from slavery, racism, poverty, dangerous neighborhoods… and trouble.

It’s understandable, but what you fear manifests. Or, more accurately, what you focus on does.

Imagine a culture with a focus on revitalizing the community, creating jobs, building networks, businesses, schools, improving yourself… Towards, not away.

Of course we see this more-easily at large scale. Compare Tel Aviv or Dubai to Gaza! Tel Aviv and our Emirati cousins run towards improvement! The other guys run away from their neighbors, from peace.

When we’re immature, when we lack faith developed and hardened over time, we run away. We run away from difficult conversations, from facing our pains and shortcomings, from doing the work we need to do.

One of my favorite Tony Robbins quotes is, “It’s not a mystery how to lose weight. You need to run away from that information.”

Food can be an escape. So can any addiction — drugs, money, work, social media, sex. These are too-often corrupted into escapes, not destinations.

It’s a lot easier to have fun with lots of people than build and maintain a stable, loving relationship with one person. It’s a lot easier to bury yourself in work than to take that plunge into the great unknown of dating, relationships, life…

The most common thing we run away from? Facing ourselves honestly.

That’s one of the greatest ironies of life: You can run away from facing your self, but you can’t escape it.

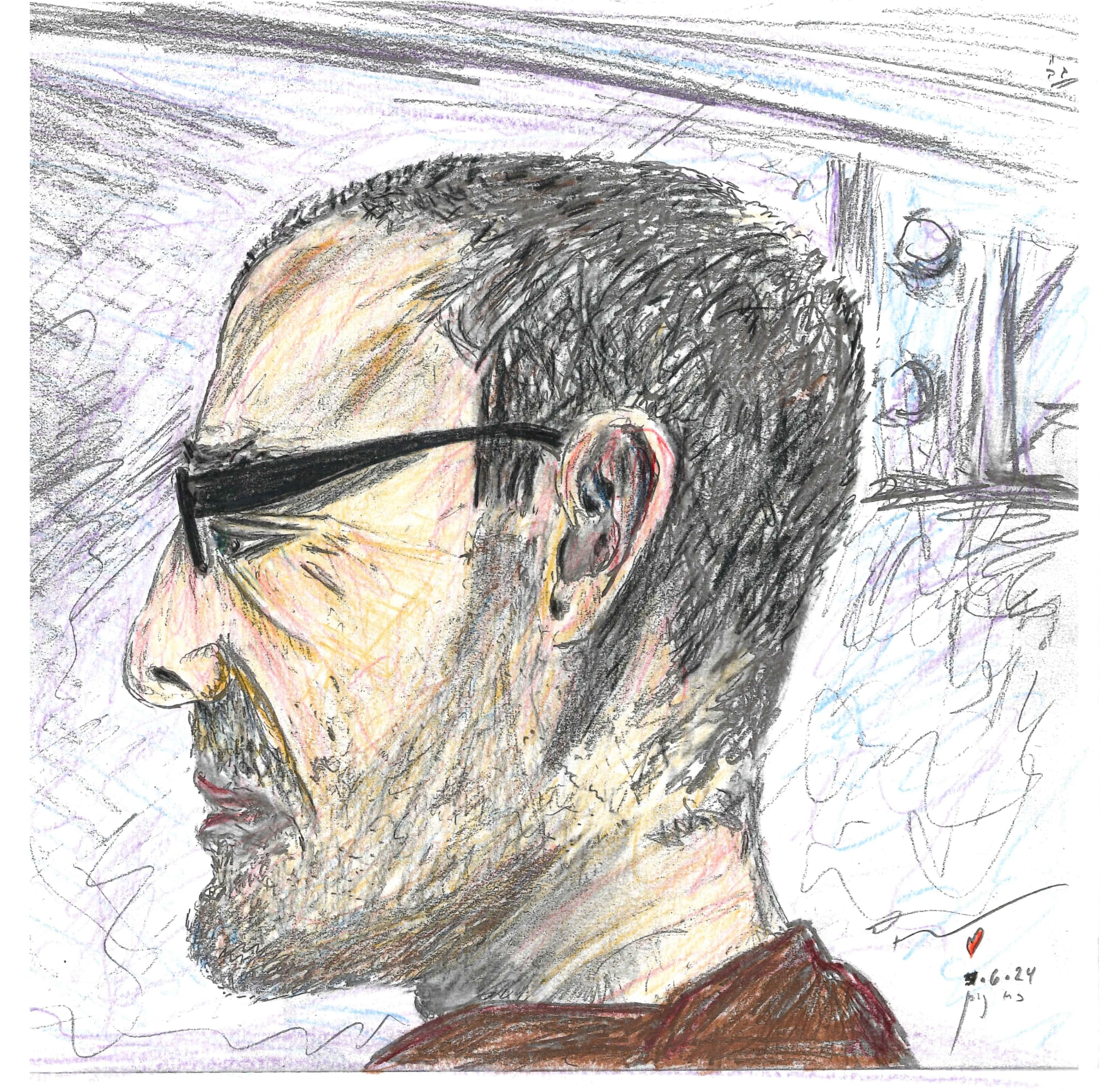

Martin bravely switched from “away” to “towards” and turned his life around inside. He was obese, and making a living dealing drugs. It’s why he’s in here. (Not for being obese — that’s clearly legal in the USA.) Now he’s one of the most-fit guys here, works out daily, has an incredible attitude of confidence, faith, and generosity, is always curious to learn, and is planning to be a fitness and mindset coach when he’s out in a few months. I’d recommend him, and bet on him.

Why? Because he’s running towards, not away.

For those who followed my social media, Martin and I began chatting about having perfect pull up form. (“Lift yourself up. Every. Single. Day.”) It’s true that how you do one thing, is how you do everything. Martin studied fitness from books, perfecting his form, and takes the same approach to business, mindset, and other fields.

Rather than “run away from the information”, rather than run from the hard work, he actively seeks it out.

This is facing your shortcomings head-on, seeing them as opportunities for growth.

Success is only found by running towards.

An executive or entrepreneur who runs away from failure will find failure. One who pursues sales will find them.

There is no success in running away. There is at-best survival, failure to thrive.

Our Soul does not want or need to run away. It is eternal, untouchable, and unbreakable.

In the depths of man-made hell and cruel “fate”, humans have composed the most beautiful prose and poetry, loved, and dreamed. This is the soul.

Job and Koheleth contemplate the fleeting and unpredictable nature of life, but they still wrote their beautiful epistles.

Viktor Frankl wrote “Man’s Search for Meaning” in Auschwitz and has lifted thousands, maybe millions, of people from their own personal and tangible hells.

The soul shines even in complete darkness. Perhaps it shines especially bright there.

When I look at recent relationships that failed, personal and business and even this case, I see parts of me and parts of others which panicked, which lacked faith, and “ran away” through sabotage, cutting people off, and, as we discussed, failing to speak up — running away from confrontations, from difficult discussions, from being vulnerable.

I remember being haunted by advice I’d read too late: “Difficult whispers avoided become painful screams.”

The Torah has many examples of this. We see how Joseph’s brothers hated him, but there’s no evidence they sat down with him, a “lad” of just 17, and tried to explain why he was upsetting them. Maturity also requires that we trust the other person is capable of hearing our complaints and adjusting accordingly, and it requires the faith that we’ll be ok if tactful honesty results in a break or argument. The soul doesn’t get hurt, the ego does. The soul isn’t afraid, the ego is.

But when we run away from these difficult conversations, what are we really running away from? Our selves. Our souls.

There’s a pattern in “toxic” relationships where one or both people lose “their voice” — their soul becomes buried under the fears and pains felt by their parts. I experienced this. I’ve likely caused this — because in turning off and ignoring my soul, surely I blinded and deafened myself to my partner’s.

We read about this last week, where Reuben cannot express his thoughts and tell his younger brothers not to kill or sell Joseph.

Prison gives you hundreds of hours every week for contemplation. If you are brave enough to face your parts, and listen for the voice that is your soul, it’s often torture, but with a pleasant resolution. In the cacophony of cries and screams, of “this wasn’t fair”, “you messed up”, “I messed up”, “I suck”, “you suck”, “you hurt me”, “I’m broken”, and on and one, you hear this beautiful, still, joyful, serene, eternal voice… your voice. Your soul.

It’s a pleasant torture.

In this week’s Torah portion, Miketz, Reuben redeems himself. He speaks up. Twice. It’s no fluke, but a new way of being. So do his brothers.

Redemption is not only possible, but likely — if you are willing to face your parts and find the light cloaked in darkness.

Last night, Rabbi Lipskar, founder of Aleph and The Shul, came to visit FCI Miami Low, and he gave us a lot of darkness. You can only turn on light.

So, too, our pains, our feelings of lack, of not being enough, of hate, jealousy, rage, betrayal, these are darkness.

They are not real. Nobody can hurt us. They can only serve as, often unknowing, agents of G-d to move us along on our path.

Rav J.B. Soloveitchik, “The Rav”, a contemporary, classmate, and friend of the Rebbe, founder of Maimonides school in Boston, and the for-years the teacher of advanced Talmud at Yeshiva University’s REITS, in his essays and talks on Purim and Chanukah (“Days of Deliverance”; MeOtzar HoRav; KTAV), delves deeply into the threefold nature of man, the darkness, the awareness of our limited nature, and our infinite light. Judaism believes these all exist, concurrently, The Rav teaches.

“God asks of man to reach maturity and independence,” The Rav teaches, “He wills man to act with courage and wisdom, allegedly as his own master.” (P. 72)

The Rav wrote often about the “lonely” nature of man, how we realize we are vulnerable and nobody can save us from the existential reality that we are severely limited, that we will die, never being able to fully understand or even explore the universe, G-d, or why we are here. The Rav explains that being brave and disciplined enough to face this daunting awareness head-on is what brings us closer to G-d.

He explains that Shabbat is G-d telling us to break from working for our material and social needs and recognize it is all ultimately in G-d’s hands. He explains, “The idea of Shabbat is man’s aloneness. And if man is alone, he is also with God.” (P. 113)

The Rav continues, “If man is completely united with the community, if he is wholly in the [public domain], immersed in the concerns of the many and not in his own needs or *in* himself, then he is liable to lose his very power, his very humanity, his original thrust and sensitivity. The fantastic resources of human creativity are not to be found in the public man, but in private man; not in mans communion with others, but in communion with himself. Human greatness and genius are to be discovered in the monologue, not the dialogue; the greatness of man is found in soliloquy, in one’s loneliness-awareness and sense of uniqueness, in one’s [private domain], the four cubits of his individualistic existence.” (emphasis added)(Ibid)

However, to be clear, as the Rav continues to expound, the Jewish way is not to solely focus inward, not to become a hermit on a mountaintop, but to take our personal connection with G-d, with our unique yet infinite Soul, and use it to help uplift others, the community, the poor, the orphans, the captives.

And not only Jews. The Rav notes beautifully, “the Jew’s heart belongs to the world.” (P. 77)

You see this with the IDF rushing to save Jews and non-Jews worldwide after collapses, Jewish doctors working to save lives of all backgrounds, even terrorists, Jewish lawyers and rabbis — and even men in prison like Brian Zater — pushing for years and years to make our Justice system more humane.

“If you had to sum Judaism up in one word,” Rabbi Lipskar said to us last night in the FCI Miami Chapel, “what word would it be? ‘Light’.”

The Jews are to be “a light onto the nations” (Zechariah (?)), a small, powerful light into the vast darknesses of the world.

So what are the lights of Chanukah? Why this of all temporary military victories (we ultimately lost the temple!), do we commemorate?

The Rav clarifies, “there is a general misconception about the motivation for the Hasmonean uprising. The revolt of Matityahu the High Priest and his sons was not a response to political pressure. From the time of Ezra…. Israel had never been politically independent…If the only issue had been political sovereignty, the revolt would never have broken out; the Jews would have continued to accept their suffering ‘with love’ and would have waited for the eventual complete redemption [Messiah]… The conflict with the Greeks was a different matter entirely. The Greeks hated the Jews’ spiritual essence, their worldview… in short,their Torah… Therefore the Greeks began to meddle with the intimate reality of human life, the Jewish people’s connection to God, and began to conduct their battle on a new ground: that of religion.” (P. 131)

The Rambam makes this clear, too: “In the era of the Second Temple, when the kinds of Greece decreed laws on Israel and annulled their customs and ways and did not allow them to engage in Torah study… then Israel was much aggrieved.” (Mishna Torah, Laws of Chanukah 3:1) (Ibid. 132)

Chanukah is the celebration of a spiritual victory, not merely a physical one.

The Rav explains what makes someone truly heroic. “They are fully conscious of their self-worth and uniqueness, and will never give up their spiritual treasures or sell their birthright for a mess of pottage…”

Unlike red-headed, brutish Esav, who sold his Abrahamic covenant to Jacob for some lentils, someone connected with G-d will never sell that connection for material goods or pleasures.

One cannot become close to this aware without running towards the Self, sitting alone, deep in the existential loneliness of being human, and facing ones parts until the Soul rings clear.

The world will challenge us, it will offer us distractions — it will show us thousands of ways to “run away” from this knowledge, as Tony Robbins says. The Rav says that should the world ask us for our material goods, as Jacob had to give to Esav for peace, we give them with humility in the aim of peace. However, should they ask us, “Where are you going? To whom do you belong as a spiritual creature?” “Then you should begin to speak a different language, the speech of a victorious hero. You should, as Jacob told Esav, proudly declare that we remain with G-d, with our Judaism.”

The Maccabees, “fought for the purity of the soul of the entire Jewish collective.” (147)

So how do we accomplish the “purity of the soul” for ourselves, for the Jewish people, and, as “the heart of the Jewish people belongs to the world,” for others?

How do we heal ourselves? Emerge from the darkness and pain we feel and observe?

(SEE PART 2)

(Continued from Part 1)

The Rav answers: “The true cure is elevating the evil, raising the defilement to the height of purity, transforming evil into grace and contamination of the soul into purity of spirit. Purification is always an elevation. We say a person ‘ascends’ from his or her impurity; that is the technical term used. When an impure person immerses himself and becomes pure, he wins not only his previous degree of purity, but much more: he becomes greater, he ascends, he is greater in sanctity. The purification process is an ascent via descent,” The Rav teaches, “… The spiritual courage of repentance, of breaking one’s will, conquering one’s desires, exercising self-control, and achieving self-elevation –

– these endow a personality with power and force.”

Facing one’s own darkness, rather than running “away” from it, is the path to elevation.

I recall, during a particularly dark time in this journey, when I questioned why I and someone I loved had descended into such dark energy, I opened a book of the Rebbe’s writings and letters. In it, was a responsa of The Rebbe, “One should not go into darkness, but if one finds themselves there, it is for the purpose of bringing light.”

At the time, I understood this to mean to spread light to the other person, to give them light, but now I see that in reality when we find ourselves in darkness, it is because we have been overcome by the darkened, hurt parts of ourselves. The purpose of the pain we feel is not to fix others, but to find and magnify the light of our Souls. To heal those hurt parts of ourselves, so that we do not hurt but help others.

The Rav, continues, “The concealed miracle of Hanukkah — the elevation of evil, the sanctification of the defiled soul and its inclusion in the realm of holiness — is perhaps the most powerful vision of Judaism: ‘And God saw every thing that He had made, and, behold, it was very good’ (Gen 1:31). If everything is good, then the good can always be saved and raised up again, even if it has been defiled temporarily.”

This is true of the land of Israel, of the Temple under the Maccabees, but surely it is also true of every human, each formed in the Image of G-d, each a part of Creation, the entirety of which is good.

The Talmud teaches that right now, when we lack the perspective to understand the good, we say, “Praised is the true judge,” but when we are completely redeemed we will say, “Blessed is the Good and who makes Good.” (src?)

Or, as The Rav taught, “In retrospective meditation, in glancing backwards, you may begin to see the reasonableness of an event that you classified as absurd and unreasonable.” (P. 14)

This, too, is the story of Joseph, which The Rav also ties to Chanukah — and which we read yearly at the same time. “God, the Eternity of Israel, has strange ways of being manifested in each person. No matter how sunk in defilement each person may be, there exists deep, deep in his soul something holy from which God spins the web of kingship.”

As we have discussed in previous essays, Judaism has no saints or perfect humans, our heroes are those who overcome their inner darkness, who run towards the light.

It is not easy, it’s frightening, the darkness inside each of us, more frightening than looking at the darkness we perceive in others. It’s so much easier easy to judge, to gossip, to blame — all things Judaism stands firmly against. “Heroic action means sacrificial action,” The Rav teaches. (P. 160)

What is a sacrifice but to give up something of ourselves? As with IFS Therapy, we do not destroy or label our parts as bad, but rather find the good and elevate them. In Judaism, sacrifice is not destruction — it is the elevation of the mundane into the holy. We do not sacrifice our worst parts, but our best, making them even better.

Sacrifice is a lonely act. Judaism forbids sacrificing others — and was unique in this. Much of Jewish law is a “fence” around mimicking the savage cultures which sacrificed others (even children) for their own salvation —

surely a failed and absurd act, more a theft than a gift.

“Even after rising to power, Joseph felt lonely; he could never integrate himself into Egyptian society. “They set on for him by himself, and for them by themselves, and for the Egyptians who did eat with them, by themselves: because the Egyptians might not eat bread with the Hebrews; for that is an abomination to the Egyptians,” we read in this week’s Torah portion, Miketz (Gen 43:32)

The Rav explains, “They needed Joseph, his talents and vision, so they tolerated him. He was the instrument used by God in order to realize the destiny of the covenantal community. Yet, for the privilege — and it is a priviledge, indeed — he had to sacrifice a great deal. he had to act with courage and determination to live through the dark night of loneliness and heroism.” (161)

Joseph, unlike those before him, had a unique test: To remain proudly Jewish and adhere to his values despite immense wealth and power. It is easy to call to G-d from the darkness when we have nothing left, harder to see the light when there are so many distractions — so many temptations pulling us “away”. Joseph succeeded at both, in the darkness of the pit, the torment of unjust imprisonment, and as a the 2nd most-powerful leader of Egypt. At no point did he give up on Abraham and Isaac’s values, at no point did he give up on his quest for peace with his brothers.

Joseph’s names for his sons, reflect these two stages of his life, the first, Menashe, named for success that would help him “forget” the pain of his father’s home, the second, Ephraim, expressing gratitude for his newfound comfort and power. Rabbi Sacks explains that because Ephraim was named from a place of gratitude, Yaakov blessed him first.

When we have much, we have much to be grateful for, and in the light, we turn towards G-d in gratitude.

The Rambam explains, “The commandment to light the Hanukkah candles is an exceedingly precious one…and one should be particularly careful to fulfill it, in order to make known the miracle, and to offer additional praise and thanksgiving to God for the wonders which He has wrought for us.” (Hilchot Chanukah 4:12)(P.170)

“In spite of everything, man does not lose his faith; he searches for God with his whole heart and soul. This is the great act of faith,” The Rav continues, “‘You shall find Him if you search with all your heart and with all your soul.’ (Deut 4:29)” (P. 175)

Searching is running towards, not away.

Reuben and Yehuda, in Miketz, also redeem themselves. Last we saw them, they were discussing throwing Joseph away, even killing him. Reuben was too afraid to voice his opinion to not kill Joseph, even though he was the oldest and in-charge! His soul was crushed by feelings of insecurity, of not being loved — false beliefs, just as we all harbor about ourselves at times in one way or another. Yehuda, too, failed to act. The brothers meant well, but they ran away from responsibility — or at best, they stayed still, hiding from it. In Miketz, they run towards it, putting themselves and their families at risk to do the right thing. Repeatedly, it is now their nature. They have elevated their parts darkened by pain and jealousy to love and light.

As with Reuben and Yehuda’s transformation, and unlike previous Jewish military victories, Chanukah (and Purim) came from inside the souls of the heroes. The Rav points out: “No prophet promised them a reward, no vision inspired them, no message gave them solace. It was an act of faith par excellence. This is their message to the generations: ‘Do not believe that our people is abandoned of God’ (II Macc 7:16).”

move along invisible paths.” (Ibid 177)

To keep moving towards. To have faith.

It is a difficult, often painful, lonely journey, dependent on us constantly returning to difficult self-examination, and brutal self-honesty, to facing our “hurt” parts which hurt others, to doing the frightening work of engaging with them, descending into the darkness, so that we may bring light. Ascent by way of descent.

Two great Jews, Jerry Seinfeld and Howard Stern were chatting about Seinfeld’s process, and how he will focus on a topic for weeks, even years, constantly obsessing with bringing out the most efficient and effective punchline — few comedians are as “tight” in their delivery, packing as many observations per-minute on a single topic.

Howard said, “That must be torture,” to which Seinfeld replied, “That’s life. Finding a torture you can tolerate and pursuing it to the best of your ability.” (Paraphrasing. There’s no google here.)

Running towards Self-improvement, towards ascent, is a pleasant torture. It is the constant meditation on G-d, on our Souls, the G-dly, Eternal part breathed into us, toward realizing that even the most painful, difficult, seemingly unfair and unjust moments of our lives, and even the “parts” which feel most pained, shamed, hurt, embarrassed, regretful, frightened, insufficient, defensive, aggressive, selfish, brutal, and a myriad of other “not good enough”

feelings, are from G-d, and that like G-d and his Creation, everything is ultimately good.

It is the elevation of those parts, and their desires and habits, into holiness, the repurposing of our urges to the best of our abilities from darkness to light that is Judaism’s mission, individually, as a people, and as a planet.

When IFS’s founder Richard Schwartz writes about comforting and coaching our “parts”, he quotes a number ancient sources and faiths, but all are predated and informed by Judaism. They’re sequels or knock-offs. And where they fall short is they diverge, as Rabbi Sacks and the Rav point out, into treating humans as unchangeable, unfixable labels, objects. In the “sequels”, and in Western culture, people become their sins, their good and bad deeds. They must wear a Scarlet Letter, a conviction, a badge, a number or label for the rest of their life. This is wrong.

The Torah teaches that we are not our material accomplishments or possessions — as Esav mistakenly believed, and as modern society often does. “We are not the best or worst thing we have done” as Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Institute for Equal Justice said in his TED talk, advocating for more humane treatment of juvenile defendants.

Judaism teaches us that we are a Soul, eternal, unbreakable, and always redeemable. We are light. We are good. It is our task to face the darkness, peel it back, and uncover the good.

Chanukah reminds us of this spiritual quest. It reminds us to run “towards” the values that are difficult but ultimately the only ones that are fulfilling.

King Solomon, aka Kohelet, the wisest man to live it’s said, who had near-endless wealth and physical pleasures, came to the conclusion that ultimately while we are to enjoy life, enjoy love, great food, life’s pleasures, these things are fleeting distractions, vanities, and the purpose of our existence is to to study, practice, and find ourselves closer to G-d and His values every single day.

It is not an easy task. It is a pleasant torture. But the ultimate reward is to see ourselves and others add a bit more light each day.

Happy Chanukah.

Ari

=============

Group Message. Draft 1.0. You may share this message. As always, check original sources.