Last night, I taught a drawing class to a room full of men accused of crimes ranging from armed bank robbery, to child porn, to drug running, to white-collar fraud, to illegal migration, to public corruption…

The Education building of FCI Miami Low looks like a small school, but with the same heavy steel doors and prison locks you see everywhere else on compound. The staff wear stab vests saying “Federal Officer” across the back, badges, large chained keyrings, walkie-talkies, occasionally handcuffs, and what appears to be bear spray. There’s no forgetting where you are, but it’s still an oasis among the buildings, and the staff genuinely care for the men here and have great rapport with them.

There are five classrooms that look just like any other, globe on the teacher’s desk included, a barber classroom ringed with barbershop chairs and tables, a “Leisure Library” with walls of dimestore novels (and sparse selection of much else) and six “DVD watching stations” where guys sit for hours watching movies, a “Law Library” ringed with computers to search Lexis Nexus and typewriters (no word processing software!), and a few well-appointed classrooms dedicated to HVAC training, plumbing, and re-entry. The re-entery classrooms are bathed in color, drowned in it actually, because it’s run by Officer Philip, who wears colorful shirts and flamboyant shoes, even bright color-coordinated K95 masks, uniforms be damned. He doesn’t just peacock, he’s got peacock feathers all over his rooms.

Most guys are in the Education building because they have to be — there’s a GED requirement here, and a shocking number of guys have not graduated high school. English and basic math classes fill the schedule. If they’re not here to take a required class, use the printer in the law library, type a motion or letter, or watch a movie, they’re there for work as a teacher or tutor.

Education has not been a priority for most men here, and for most it’s been presented as a burden rather than an opportunity. Surely, that’s one reason many have ended up in prison. As Zater says, you enter prison in your mind long before they put the handcuffs on you. The trick is to escape the mental prison so you don’t come back to the real one.

That’s the main reason I offered the class.

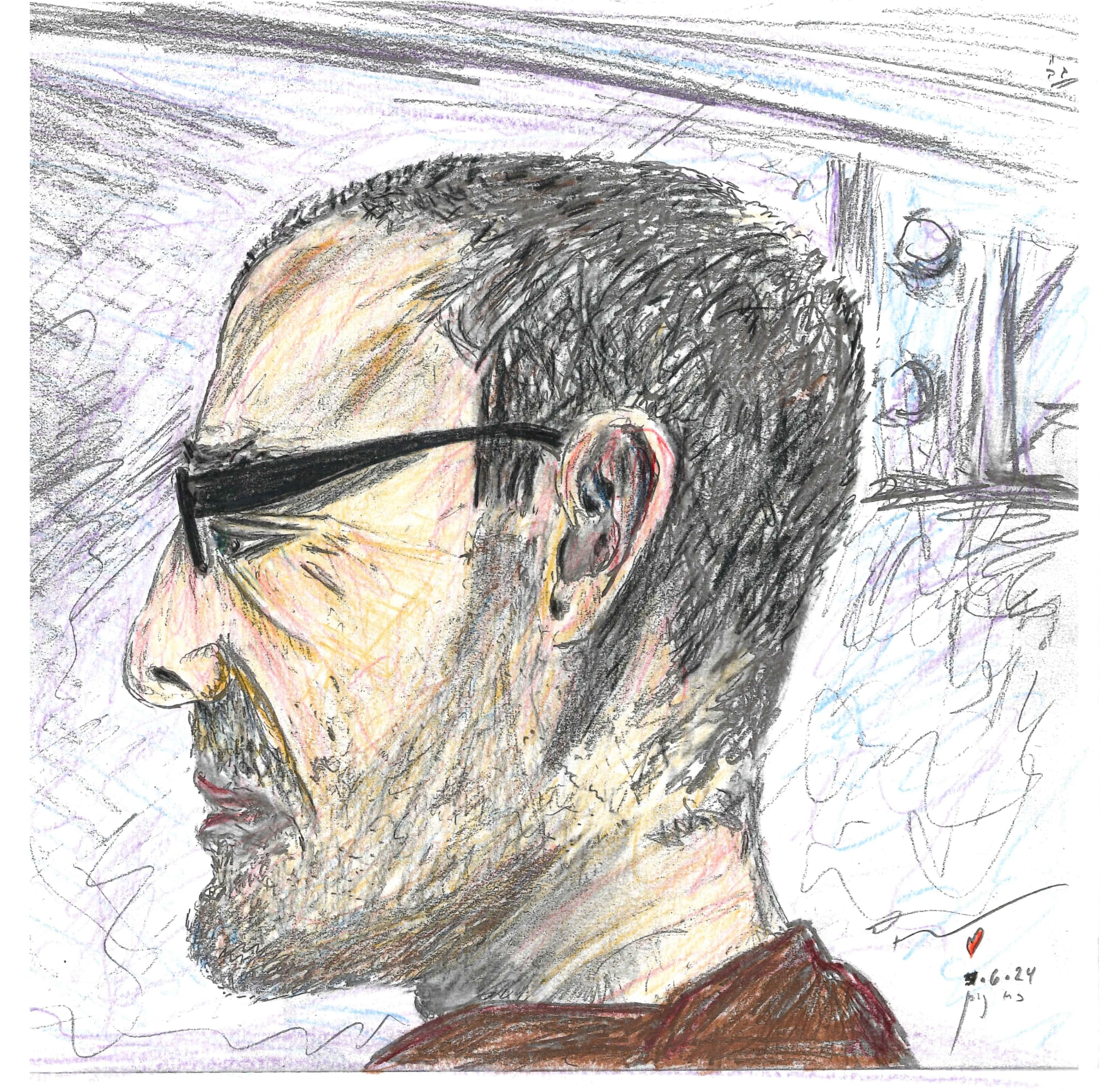

There has not been an art class here in years, if ever. Yet, whenever I would sketch on a scrap of paper while waiting for an appointment, guys would ask if I were an architect, often in Spanish, and others would watch pensively over my shoulders. Young and old, black and white and Latin and Hispanic, clean shaven and bearded, tattooed and not… it seemed to interest everyone. Then again, there’s not much else to do here, and plenty of time to fill.

I’ve written about “drawing in prison” and how it brings guys over who talk about their art, education, and dreams.

I’d always offer to show them the basics, and through that I realized there was a real hunger to learn.

What has carried me through this experience best is the Jewish idea that we are never “stuck” in a place, but that wherever you are, G-d put you for a reason, for yourself and others’ growth and elevation. The Torah, especially Bereishit (Genesis), which we are reading now, is full of examples of “unfortunate turns” that lead to the growth of our forefathers and mothers and the the birth of our nation.

In fact, in this week’s portion, VaYishlach, we get our name Israel, when Yaakov (Jacob) “wrestled with G-d and man and overcame”. The battle over “why” we are here, why and how we face challenges and obstacles, how our “real world” interactions should interplay with our G-dly mission in life is the very essence of Judaism. Fear — of the natural world, scarity, & man-made threads — versus faith that with G-d we shall overcome.

Yaakov comes “face to face” with G-d, in an all night mental and spiritual battle, and immediately switches from a fearful man hiding his family and wealth over a river to one of faith, walks right up to his brother, Esav (who swore to kill him 22 years prior for “stealing” his birthright blessing, and returns the blessing. The blessing was for natural fortunes and power, but Yaakov returns it saying, “I have everything,” because he realized it’s through G-

d, not through rain or dew or physical strength that our fortune comes.

Rabbi Lord Sacks explains frequently that the Jewish people put their hope on God, not physical power or phenomenons, and that we learn this from our ancestors in Genesis. It was not despite the obstacles and threats, but the faith he forges *because of them*, that Yaakov reaches the level to be the namesake of the Jewish people, Bnai Yisroel, the sons of Israel.

So being stuck in prison, forced to draw with cheap pen on random printer paper, had to be for a reason. The more guys asked about my drawing, the more faces lit up when I showed them tricks and had them try it themselves, the more teaching this drawing class felt like something I “had” to do. This gift, to be able to draw, and to have parents who invested in art classes throughout my life, felt like something G-d did not give me only for my own comfort — though surely drawing in prison and outside has been meditative and healing, and I highly recommend sketching your dreams and ideas for a few minutes every day.

The more guys told me, “I can’t draw,” “I have no talent,” “I’m not an artist,” the more important it felt. Prison is full of men who have been told their whole lives what they can’t do, how they’re not worthy, or special, or lovable.

In fact, that’s why most of us are here, when you get to the core. Anything you can do to lift another man up, to show him he’s special, capable, and able to create, add value, and help others, is G-dly, important work.

The entire structure of charity in Judaism, Maimonides explains, is to help men lift themselves up. In fact, Judaism does not have prison except for imminently dangerous men or men possibly facing the death penalty (a near impossibility to dish-out, btw. If they put 1 man to death in 70 years they called themselves a “bloody court”.

In the USA our error rate for death penalty convictions is about 1-in-10!), instead, men work off their debt for a maximum of 6 years, and they are not kept from their families while doing it. They must be treated with dignity, and it’s a requirement to send them off with enough to stand on their own and start life anew. What a contrast to our prison systems.

So, we must do what we can, in here, and from the outside, to restore humanity and hope, to help men gain skills and beliefs so they can stand on their own with confidence and self-love.

It took weeks to get approval — and I faced a ton of rejection (which only encourages me). First we tried at Rec, where there’s a painting and clay room, but no instructors, and they balked — they didn’t want a gathering to deal with. Education wouldn’t go forward with a class unless we created “tests” for the guys to pass under an “ACE” (Adult Continuing Ed) program, which would then take months to be approved. Finally, I pitched the head of Education, Officer Gadson — a really great guy who works incredibly hard to bring new education opportunities to the guys here — on doing it unofficially, no credit or certificates given, and he agreed to try it.

On Wednesday, we posted hand-drawn signs around the compound (there’s no graphics software or even a word processor!), and Officer Gadson shared the sign on the Trulincs Bulletin board.

All day Wednesday and Thursday guys came up to me asking about the class, and telling their friends, “That’s the guy offering the drawing class!” It felt odd to be “known” in prison, but it’s a small world here after a while anyway — and that’s a much better way to be known than some guys!

Some guys fell to their resistance, talking themselves out of trying (we’ll get them!), but we still managed to fill a classroom — an incredible thing with just a day’s notice.

We had 14 students, some of whom you’ll recognize from previous emails, like Zater and Will, and John my literally next-door neighbor, but most who saw signs and showed up. This is remarkable for an “unofficial” course.

The guys who came, came to learn.

I created a worksheet and practice sheets, and made notes for myself to keep the class on track in case nerves or distractions hit.

The guys got the concepts well, most did excellent drawings themselves, and all told me they enjoyed it a lot and There was a bittersweet moment when I told them I didn’t know because we hoped to get good news about me being released to home confinement next week, but that I’d arrange to get a volunteer teacher or come back as a volunteer to teach when allowed. It was deeply moving when they replied with smiles that they hoped I didn’t come back — that I’d be home. After the class some guys come up and said they were happy to hear I could be leaving, but “wished we had more time together.” There’s a lot of kindness here.

We didn’t have rulers to make straight edges so guys used the Federal Prison ID cards we’re required to carry at all times — I do this a lot, too.

A few guys had previous art experience, but most did not. At the end of the class about half said they felt confident that they could draw in 3D, while the rest said they felt they’d get there with daily practice.

We covered: One, Two, and Three-point perspective; Vanishing points; Perspective lines; building 3D buildings; drawing trees, poles, lamps, etc. that get smaller as they go towards the perspective lines; drawing windows and doors; dividing a surface into halves/quarters using an X connecting its corners and going from the midpoint to the vanishing points; figuring out how to “predict” correctly the size and shape of identical boxes laid-out in 3D space; shading; making a 3D streetscape with an intersection (buildings that wrap around a corner); drawing curves and round shapes in 3D… and even how to draw a straight line without a rule (move your arm and the paper, not your fingers).

All in about 90 minutes.

I passed around a book my dad had sent in on perspective drawing, and guys wrote it down to have their friends and family send them a copy. They were eager to learn more.

More importantly, we reinforced the idea that nearly anything in life can be learned by finding a teacher, book, or video that shows you the steps or “hacks” to get the basics. I gave as an example how I was able to learn to do pull ups (“Every. Single. Day.”) from YouTube videos which showed excercises that lead up to being able to do one. Guys in the class shared other examples, from losing weight, to learning a language. Life hacks.

You could see guys faces light up as it “clicked” for them, the revelation that things which seem “impossible” are easy to overcome when you believe (a) anything could be learned, and that (b) daily practice brings mastery.

It was a class about perspective, but not just the drawing kind.

The class was a lot of fun and seems to have brought a lot of great energy to the place.

After class, John and I thought-up a children’s book that would explain to his four-year-old son and others with fathers and mothers in prison the journey he’s taken through prison through the eyes of a boy sent to his room for making a mistake (conspiracy to distribute stolen cookies), who uses his time to read, exercise, meditate, and help the elderly folks in his house, just as John does here. Today, John came up to me excited, having written most of the book. It’s a great one, and in John’s style, has subtle cultural references the adults reading the book to their kids will understand.

The Education staff asked when I’d do the class again, so I hope we’ve a precedent where they have outside volunteers come teach art and other topics. G-d willing I’ll be “outside” soon and will help recruit and build a program of volunteer teachers.

Step-by-step, we’ll elevate the experience for folks in prison, and in doing so, uplift ourselves.

How we treat those most vulnerable, ostracized, and down-on-their-luck reflects more on us than them.

Prison exists as bars and windows in the minds of most, but in reality, like everything in life it exists as a conversation. We can choose for that conversation to be one of judgement, condescension, blame, and shame, or our prisons can say, “You are lovable, we love you, and we are here to help you heal and grow.”

Yaakov’s spiritual wrestling with “man and G-d” is much about the difference in how we see the world and how G-

d does. As Rabbi Sacks explains so well, Yaakov was an imperfect hero, as all of Judaism’s heroes are. He loved one wife and her child (Rachel and Yosef) more than another’s (Leah and her sons) and it had profoundly

(see PART 2…)

(Part 2)

leading to Yosef (Joseph) being nearly-killed by his brothers, sold as a slave to Egypt, and ultimately to the Israelites being enslaved for hundreds of years.

It is understandable that Yaakov struggled to love Leah, whose father snuck her into his wedding tent in the dark of night in place of Rachel — whom he dreamed of marrying and loved so much that working 7 years for her hand seemed like a day passing — but the results remain the same. Leah and her children were human, too, and they needed love. As a result, Leah’s firstborn, Reuven, lacks the confidence to share his inner thoughts, recorded in the Torah, with his own brothers that they should not harm Yosef. Reuven doesn’t act on his inner thoughts, his soul, and stop his brothers during their jealous rage, and their decendants suffer for hundreds of years as a result.

The Torah is teaching us about the importance of Self-confidence and Self-love. Self with a capital “S”, or as we might say it, our Soul.

Unlike Yaakov, Rabbi Sacks explains, G-d loves us unconditionally. Not regardless of our imperfections, but because of them. This should give us tremendous confidence. G-d loves us, always. Surely if He does, we should.

With that confidence, we can listen to our Soul instead of our ego. We can choose the right paths over the easy ones, we can express our feelings, we can be vulnerable, transparent in our “imperfections”, honest about our aims, and have faith that things will work out for the best.

It’s not always easy — in fact, it’s a wrestling match — but like the drawing class, there are steps, and teachers, here to help us. G-d has given us “everything” we need.

Respectfully, one of the great disservices Christianity (or at least some popular branches) did to the world — one so antithetical to the message of the Torah — is to present “perfect” characters, “saints”, humans without sin, as those to which we should inspire. The Torah has no saints. What makes humans heroic and lovable is that our flaws, insecurities, fears, and wounds do not prevent us from elevating ourselves and others, from facing the challenges of life and the daunting spiritual tasks before us “face-to-face”, with unrelenting faith that there must be a reason, and there must be salvation through our efforts.

This week’s Torah portion is about perspective. Literally. Yaakov is said to have faced G-d, “face-to-face”. He then faces his brother, Esav, who last threatened to kill him over a blessing, a hunter and warlord accompanied by 400 men, and says that seeing his face is like “looking into the face of G-d”!

The real lesson of this week’s Parsha, and of my time in prison, and the years of fighting relentlessly to avoid “facing” it, is that we must look at ourselves and others as if we are looking into the face of G-d, because we are.

We are all G-d’s children, we are all worthly of love, and it’s our task to remind one another of this, through words and actions. This is the path to true confidence, and surely the path to peace.

Wishing our brothers and sisters in Israel and all over the world true Self-love and unconditional love for all.

Shabbat shalom.

With love, Ari =================

leading to Yosef (Joseph) being nearly-killed by his brothers, sold as a slave to Egypt, and ultimately to the Israelites being enslaved for hundreds of years.

It is understandable that Yaakov struggled to love Leah, whose father snuck her into his wedding tent in the dark of night in place of Rachel — whom he dreamed of marrying and loved so much that working 7 years for her hand seemed like a day passing — but the results remain the same. Leah and her children were human, too, and they needed love. As a result, Leah’s firstborn, Reuven, lacks the confidence to share his inner thoughts, recorded in the Torah, with his own brothers that they should not harm Yosef. Reuven doesn’t act on his inner thoughts, his soul, and stop his brothers during their jealous rage, and their descendants suffer for hundreds of years as a result.

The Torah is teaching us about the importance of Self-confidence and Self-love. Self with a capital “S”, or as we might say it, our Soul.

Unlike Yaakov, Rabbi Sacks explains, G-d loves us unconditionally. Not regardless of our imperfections, but because of them. This should give us tremendous confidence. G-d loves us, always. Surely if He does, we should.

With that confidence, we can listen to our Soul instead of our ego. We can choose the right paths over the easy ones, we can express our feelings, we can be vulnerable, transparent in our “imperfections”, honest about our aims, and have faith that things will work out for the best.

It’s not always easy — in fact, it’s a wrestling match — but like the drawing class, there are steps, and teachers, here to help us. G-d has given us “everything” we need.

Respectfully, one of the great disservices Christianity (or at least some popular branches) did to the world — one so antithetical to the message of the Torah — is to present “perfect” characters, “saints”, humans without sin, as those to which we should inspire. The Torah has no saints. What makes humans heroic and lovable is that our flaws, insecurities, fears, and wounds do not prevent us from elevating ourselves and others, from facing the challenges of life and the daunting spiritual tasks before us “face-to-face”, with unrelenting faith that there must be a reason, and there must be salvation through our efforts.

This week’s Torah portion is about perspective. Literally. Yaakov is said to have faced G-d, “face-to-face”. He then faces his brother, Esav, who last threatened to kill him over a blessing, a hunter and warlord accompanied by 400 men, and says that seeing his face is like “looking into the face of G-d”!

The real lesson of this week’s Parsha, and of my time in prison, and the years of fighting relentlessly to avoid “facing” it, is that we must look at ourselves and others as if we are looking into the face of G-d, because we are.

We are all G-d’s children, we are all worthy of love, and it’s our task to remind one another of this, through words and actions. This is the path to true confidence, and surely the path to peace.

Wishing our brothers and sisters in Israel and all over the world true Self-love and unconditional love for all.

Shabbat shalom.

With love, Ari

=================

Group message.

Draft 1.0.

You may share this letter.